"A Very Dangerous Game" by Gordon Leveratt

29 October 2024

Introduction

Way back in 1984, Tom Clancy’s first novel “The Hunt for Red October” was a phenomenal success; so too was the film starring Sean Connery. They tell the story of a Soviet submarine captain going rogue in a “Typhoon” Class SSBN, as he tries to elude her hunters across 4000 miles of ocean to defect to the USA.

At the time I was commanding HMS Swiftsure, a nuclear attack submarine (SSN) or “hunter-killer” whose role is to seek and in war pre-emptively destroy enemy submarines and ships.

Clancy did a terrific job authentically describing the deadly game of hide and seek played by submarines for, ever since the 1950’s and the start of the Cold War, British, American and Russian submarines (called boats in “The Trade”) have been stalking one another in the ocean depths.

Background

During WWII the Germans sustained staggering U-boat losses – 785 of the 1162 boats constructed and 30,000 crew members – and though too late to affect the outcome of the war they had begun building revolutionary designs.

At war’s end it was decided that the UK, US and Russians should each have 10 of these later boats before scuttling the rest. Hitherto, Russia had little experience of ocean warfare but soon they began to massively expand their navy to threaten the West’s sea lines of communication.

In May 1955, the Warsaw Pact was created to counter NATO and the Cold War turned nasty as the Soviets were testing nuclear weapons in the Barents Sea for eventual deployment in their ballistic missile firing submarines (SSBNs).

The Threat

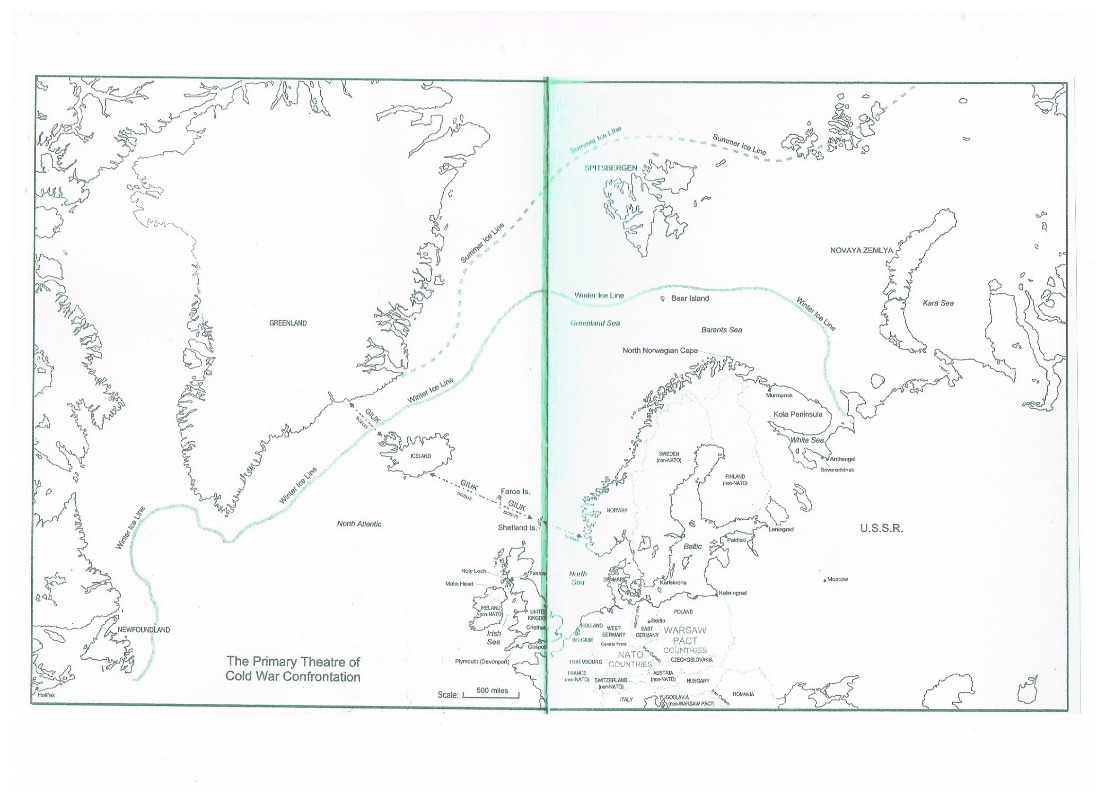

During the following 46 years of the Cold War (Cold War map below) the Soviets produced 727 boats (235 nuclear powered) including the largest ever built, the fastest, and the deepest diving.

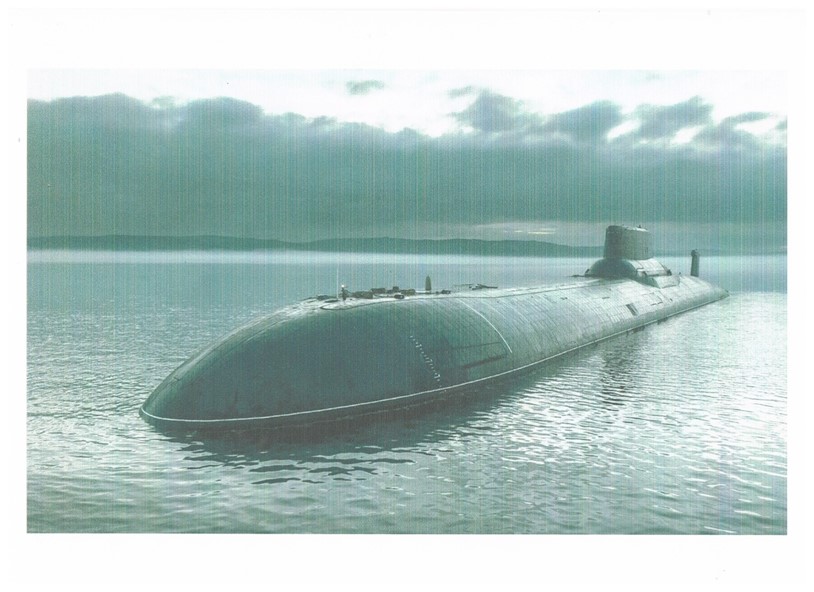

In my day (1964-1988), the Soviet SSBN threat was posed by three main classes - Yankees (34 boats with a missile range of 2500 km); Deltas (43 with a missile range of 7700 km); and Typhoons (6 with a missile range of 8300 km). Most of these boats were in the Northern Fleet based in the White Sea’s Kola Inlet and the latter two classes could threaten Western cities without leaving the Barents. Additionally, the Soviets also had a large number of SSNs, SSGNs (cruise missile boats) and diesel-electric boats (SSKs) plus a large surface fleet.

Soviet Typhoon Class SSNB

The Environment

The ocean is a noisy place due to storms, earthquakes, ice, fish and animals etc but human activity – shipping, seismic surveys, cable laying, and drilling has increased the noise level dramatically.

All noise sources vary in loudness, duration and frequency. For example, whales make different calls for navigation and socialising, all at relatively low frequency (1Hz to 1Mhz).

Submarines also emit noise due to internal machinery and the propulsion plant much of which are also low frequencies which potentially travel great distances (hundreds of Km) depending on the water conditions. Significantly, every submarine (and ship) has a unique acoustic signature enabling classification.

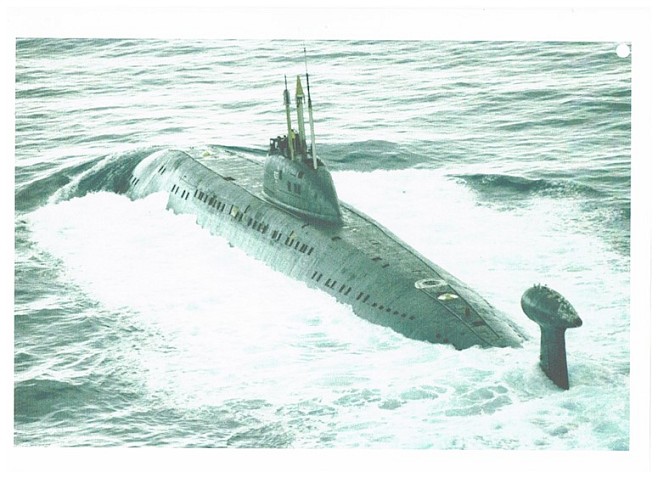

Soviet Victor III SSN

Countering the Threat

In the 1950’s, to exploit submarine noise the US laid a secret Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) of hydrophone arrays on the sea bed principally at strategic points e.g. the Greenland/Iceland/UK Gap, to act as a “burglar alarm” to detect Soviet boats breaking out into the Atlantic.

Then in 1954 America launched the world’s first nuclear submarine, USS Nautilus; later she gained fame when she surfaced at the North Pole on 3 August 1958 - a place unreachable by diesel boats. By then the Soviets had just launched their first nuclear, a November Class SSN.

Britain now lagged behind in submarine nuclear technology and though HMS Dreadnought, an SSN, was under construction the reactor plant was still in design. Fortunately, with special agreement, an American propulsion plant was fitted enabling her to be launched in 1961, sooner than expected.

In the early days SOSUS, augmented by submarines, ships and aircraft, proved successful. For instance, during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, Soviet submarines were tracked as they approached the US Eastern Seaboard and three SSKs were hunted to exhaustion and forced to surface in the Caribbean. Also, but for SOSUS, the whereabouts of USS Scorpion (a Skipjack Class SSN) might never have been known. Returning home from the Mediterranean, Scorpion was diverted to surveil Soviet naval units south of the Canaries. On 21 May 1968, a SOSUS station in the Azores detected two explosions a second apart and when Scorpion subsequently failed to check in she was presumed lost and a search ensued; her shattered wreck was eventually found that October 3000 metres down on the seabed. The exact circumstances of this tragedy are unknown but a cataclysmic event must have caused her to implode with the loss of 90 souls.

HMS Dreadnought made headlines when she surfaced at the North Pole on 3 March 1971. I joined as her Navigator two months later; she still had a reminder of the US’s contribution - a bulkhead marked “Check Point Charlie” limiting access to certain areas!

HMS Dreadnought at the North Pole

Going to the North pole was good PR but operating under the ice cap was essential as Soviet SSBNs (and SSNs) were now patrolling there and could launch ballistic missiles by hovering in polynyas. However, the environment is hostile and fraught with danger for submarines especially if a fire or flood occurs.

In 1976, when HMS Sceptre (SSN) went to the Pole I accompanied her part of the way in HMS Narwhale, a diesel boat, which could only make limited penetrations under the ice because of her need to snort to recharge batteries. Even so, it was an amazing experience.

Decommissioning HMS Narwhale – May 1977

Deep Water Operations

Eventually, the Soviets learnt both to quieten their boats and improve their sonars – mainly through knowledge acquired by industrial espionage, “legal spies” with diplomatic cover, and sadly UK/US traitors.

However, the introduction of towed arrays was game changing. A hydrophone array towed at the end of a cable (making the SSN some 500 metres long) together with enhanced signal processing enabled many more contacts to be detected and classified (mating whales and even low flying aircraft) often at long range (60-100 km or more).

Trailing a submarine can last hours and even days often relying on a single, intermittent and weak tonal. Every slight change in received frequency (0.1Hz) indicates a target alteration in course or speed (or both) due to Doppler shift. Own manoeuvres also effect the received frequency. A simple illustration of this phenomenon is a car siren; as it approaches the sound pitch (frequency) is higher than when it passes and goes away.

Target bearing and range can be progressively refined using sprint and drift tactics but depth (unless it is a snorting boat) generally is unknown. Soviet bombers, like ours, patrol at low speed but they are big (a Typhoon is 48,000 tons submerged) and have a large turning circle. A trailing 5000 ton SSN must either follow the target round when she turns or remain outside the turn to avoid detection or worse still collision. Trailing a Soviet SSN is easier because they tend to patrol at higher speed and thus are noisier but some use a “Crazy Ivan” ploy of suddenly turning back at high speed to catch a trailer unawares!

HMS Swiftsure

Other Scenarios

In April 1982, the Argentinians invaded the Falkland Islands and South Georgia, both British Dependencies. As part of the UK’s response five SSNs and one SSK (with marines embarked) were sent 8000 miles to enforce a 200 mile Total Exclusion Zone (TEZ) around the islands.

The British were keen to lure out the only Argentinian aircraft carrier as she posed the biggest threat but instead, HMS Conqueror found and stalked the cruiser “Belgrano” with two escorts. Controlled via satellite communications from Fleet Headquarters at Northwood, Conqueror trailed the enemy for 30 hours awaiting approval to attack. Eventually it came and on 3 May, Conqueror fired three Mk 8 torpedoes from 1400 metres whilst at periscope depth; the first and second hits were observed before the SSN evaded fast and deep.

The sinking of the Belgrano with the loss of 321 souls (201 in the ship and 120 of exposure in rafts) was publicly controversial because she was outside the TEZ but the sinking probably saved hundreds of British lives for afterwards the Argentinian Navy ceased to threaten.

SSNs also provided early warning of air attack by lying off Argentinian airfields and reporting by satellite link whenever enemy aircraft took off and landed. Immediately, after the war SSNs continued to patrol in the South Atlantic and whilst driving HMS Swiftsure - I spent 126 days patrolling there and seldom been so bored!

Special Intelligence Operations

The UK had sent diesel boats into the Barents before the start of the Cold War to monitor the build-up of Soviet naval forces but did not have the resources to do this continually. Eventually, the US/UK “special relationship” also embraced surveillance operations in sensitive waters. These patrols require political approval at the highest level and therefore remain largely secret.

Remaining in the vicinity of potentially hostile Soviet units for long periods is highly demanding but with intelligence experts embarked a large amount of unique information can be covertly obtained. For example, a submarine’s/ship’s acoustic signature is best obtained by getting directly underneath a target to remove Doppler and then recording the base frequencies of all running machinery. This ploy is usually combined with an “underwater look” when the periscope is raised to examine under hull features.

It is an eerie feeling lying just 2-3 feet under a large ship but it is less risky than it sounds though extra care is needed against a surfaced submarine that may suddenly dive on top of you!

Almost inevitably there been close misses and the occasional collisions but I am only aware of two involving UK boats. In October 1968, HMS Warspite (SSN) collided with the stern of a Soviet Echo II Class SSN when trailing her. And on 23 May 1981, HMS Sceptre collided with a Delta III Class SSBN. Although Warspite and Sceptre sustained significant damage they managed to get home safely. Icebergs were blamed for both incidents!

Postscript

Although I resigned my RN commission as a Captain in 1988, to follow a very different path I am privileged to have commanded two submarines and being appointed to command HMS Coventry – a new Type 22 frigate - during the height of the Cold War.

On HMS Swiftsure’s Bridge Leaving the Clyde

On HMS Swiftsure’s Bridge Leaving the Clyde

The Cold War is over but tension remains as high as ever but now there are more participants worldwide as many more nations possess nuclear submarines.

Currently, the Russians have some 58 nuclear boats including 11 SSBNs and 17 SSNs. By contrast the US has 14 SSBNs, 29 SSNs and 4 SSGNs, and the Brits have 4 SSBNs and 6 SSNs. The US/UK boats remain quieter and have the edge.

Right now one of our SSNs will probably be trailing a Russian submarine somewhere in the ocean depths and another might be operating in sensitive, shallow waters. In all instances these boats are playing a deadly game in frightening isolation where the dangers are routinely real.